Far Too Many Felines

Kauai County Council Tackles Huge Problem of Feral Cats

By Hob Osterlund, Safina Center Senior Fellow

Albatross hiking down a cliff. Photo ©Hob Osterlund

On March 9, 2022, the Kauai County Council voted unanimously to pass Bill 2842, which prohibits feeding and abandoning cats on County property. It also prohibits abandoning cats on private land without a landowner’s permission. The bill was controversial, and generated more than twelve hundred emails—nearly 90% of them in support. On 2/10/22 The Garden Island News reported “Of 1,235 relevant submissions to the Council in January and February, 1,103 expressed support for the Bill.” The San Francisco Chronicleʻs online publication SF Gate describes the issue and the passage of Bill 2842.

It's been a long slog from the onset of discussions related to this issue. In 2014 the County hired a professional facilitator to convene a volunteer Feral Cat Task Force consisting of representatives from the Kauai Humane Society, representatives from state and federal wildlife agencies, Kauai Albatross Network, Kauai Ferals (now called Kauai Community Cat Project), and community members. The FCTF met several times and ultimately produced a final report. Although there were many points of contention in those meetings, in the end all members agreed on one singular goal: zero feral cats on the landscape.

The population of homeless cats is difficult to determine, but in 2014 a representative from Kauai Ferals made a back-of-the-envelope estimate of 15,000-20,000. It’s conservative to estimate the population has increased to at least 25,000 in the subsequent eight years.

Feral cat near albatross nest. The chick was killed shortly after the photo. Photo ©Hob Osterlund

Why so many? Sometime back in the 1990s, the concept of “Trap-Neuter Release” (TNR) was introduced in the United States, and organizations such as Alley Cat Allies and Best Friends Animal Society continue to actively promote the idea. They consider outdoor cats to be “citizens of the natural landscape” and to have a “vital environmental role.” Best Friends’ byline is “Save them All” and photos typically depict adorable, healthy kittens.

You have to ask yourself how much corporate support underwrites TNR and the “Save Them All” theme. Best Friends’ corporate partners include Acana pet food, Airvet, Fresh Step (which reports donating “millions of dollars and tons of litter to over 1400 shelters”), Pawz (which donates 10% of profits to no-kill shelters), and Central Garden and Pet (which gave “one million in product donations in 2020.”)

All these organizations make abandoning cats sound like a swell idea. Good for us, good for conservation, good for cats.

Along with the “no kill” theme of countless shelters, however, these claims are terrible policy for cats and lethal for wildlife.

Homeless cats in the U.S. number in the millions. The American Bird Conservancy estimates a population of 100 million feral cats, and those felines kill over 2 billion birds every single year.

Feral cat reaches to try to catch an endangered Hawaiian duck. Photo © Hob Osterlund

Nor is homelessness good for cats. The Pet Assistance Foundation in California estimates only 10% of kittens born in southern California will end up having a human home. “Countless cats are abandoned in the streets...only to be slaughtered in traffic or die a lingering death. Others fall victim to unspeakable cruelty,” they report.

In strong testimony supporting Bill 2842, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) agreed. “As an animal protection organization, PETA condemns cat abandonment, whether or not the animals have been sterilized, because of animal welfare concerns. Abandoned and homeless cats endure harsh lives, and they inevitably die in slow and painful and/or terrifying and violent ways. Our office fields countless reports of incidents in which cats—including those “managed” in TNR programs—suffer and die in terrible ways because they’ve been left to fend for themselves outdoors. They’re forced to fight daily battles against internal and external parasites, deadly contagious diseases, dehydration when their water sources evaporate or are polluted, speeding cars, loose dogs, and malicious people—battles that they predictably lose. On a daily basis, our cruelty caseworkers handle cases involving homeless cats who have been abused or killed by property owners or neighbors who simply didn’t want the animals there, regardless of whether they were sterilized.”

Cat on cliffside hunting in seabird nesting colony. Photo ©Brett Mossman

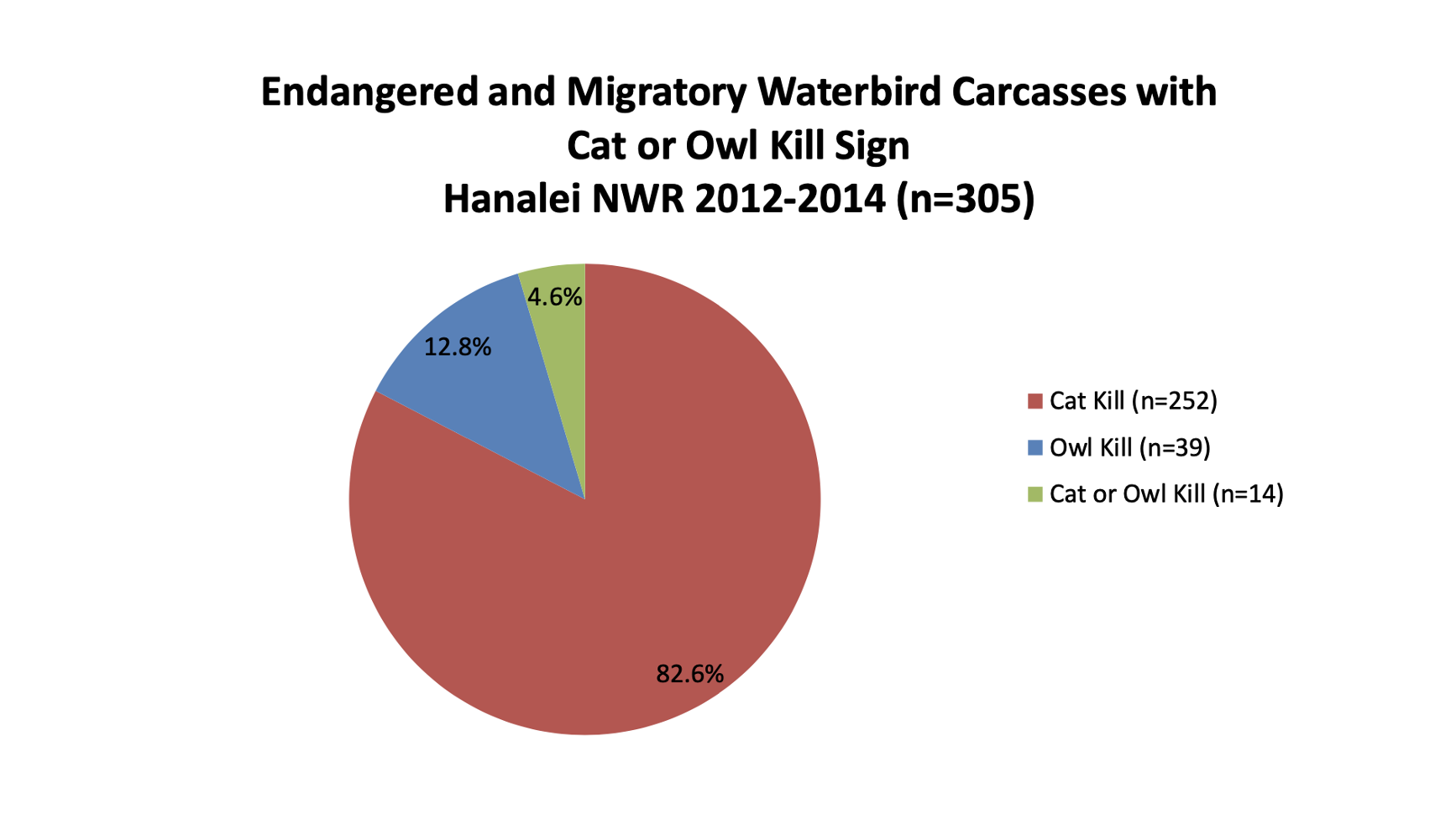

On Kauai, predation by feral cats is particularly tragic. Here we have a good number of endemic species—meaning they exist nowhere else in the world. Some of these populations are down down to approximately one thousand individuals, so any death inflicted by any invasive predator is a big loss. Hanalei National Wildlife Refuge, which protects five species of endangered wetland birds, counted 252 deaths from cat predation in a two-year period. Among Mōlī (Laysan albatross), thirteen chicks were killed in the first week of hatch alone—represent half the nests in that colony.

High percentage of predation of endangered wetland birds by cats in Hanalei Refuge

Greater Good Charities and their “Good Fix” project is advertised thus: “Good Fix reduces human-animal conflict and the burden on animal shelters to euthanize unwanted pets. The impact? Lives saved.” But which lives? Certainly not birds and monk seals, the latter of which die from toxoplasmosis from cat feces. And since the Kauai Humane went “no kill” a couple of years ago, no cat lives are predictably saved by TNR either.

Nor does TNR reduce the population of homeless felines. In recent visits, Good Fix reportedly spayed and neutered somewhere in the vicinity of 2500 cats. When I called the Kauai Humane Society last week, they were unable to identify how many of those cats were pets and how many were feral. Until we have access to that data, letʻs guess 50% of them were pets, 50% feral. If that guess is accurate, it would equate to only 5% of Kauaʻi feral cat population, which would make no dent in the overall reproductive rate of the other 95%. And even if 100% of the sterilized cats were feral, 10% is not significantly better.

What about the idea of a cat sanctuary, as suggested by some? The Kauai Animal Welfare Society has leased acreage and made a proposal in support of such a place.

As long as they have an environmentally safe plan for waste disposal (which is not currently mentioned in their proposal), a KAWS sanctuary is a good idea. But let’s be clear: even at max capacity of 350, it would house only a small percentage of the feral cat population. It’s also a very expensive proposition. The KAWS proposal suggests their costs will be about $1500/cat/year, and all of it would have to rely on donations. Even if Kauai County had an extra half-million dollars every year, and given a multitude of economic, housing, medical and social problems facing the island, feeding 350 feral cats would not remotely register as a priority.

Bill 2842 represents progress toward reducing the population of homeless cats on Kauai. Will it be enough to save the threatened and endangered monk seals and native birds? Only time will reveal its impact. But endangered wildlife doesn’t have time to wait, so additional solutions are sure to come.

Homeless cat stalks an endangered Hawaiian gallinule. Photo ©Hob Osterlund