Stories from the Sea: Nuclear Reactors, Mountains, and Dead Zones

By Safina Center Fellow Raffi Khatchadourian

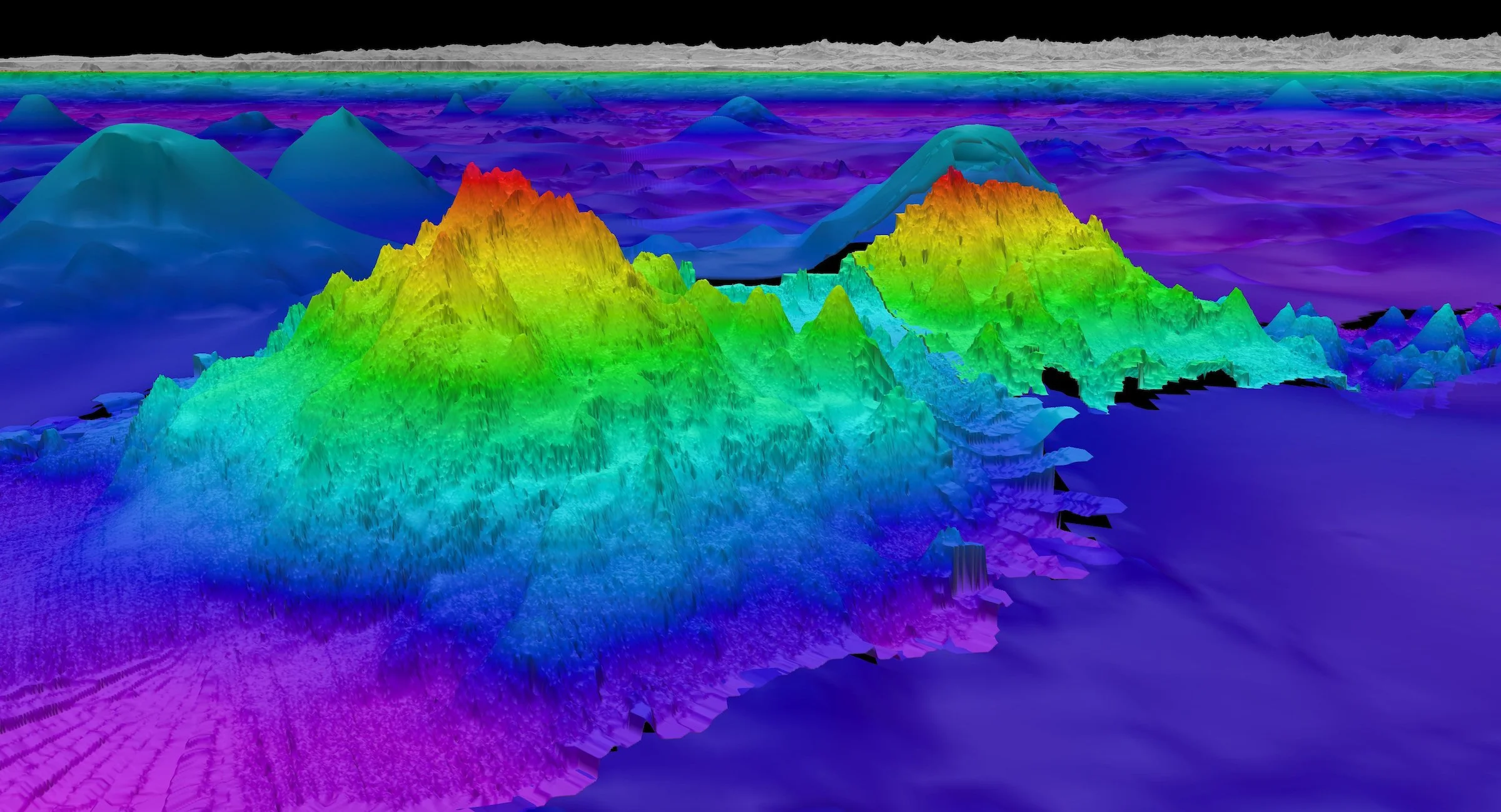

The largest of the four seamounts recently discovered by Schmidt Ocean Institute experts is 2,681 meters tall, covers 450 square kilometers, and sits 1,150 meters below the surface. ©Schmidt Ocean Institute

As a fellow at the Safina Center, I've started following ocean-related news more carefully, and I’d like to share some of the stories crossing my radar. One recent item is about Russia's state-run atomic-energy corporation, Rosatom, and how it just signed an agreement with a province in Russia's Far East to build a floating nuclear-power plant in the Sea of Japan. Russia already has constructed a floating nuclear-power plant, the Akademik Lomonosov -- the only one of its kind. It has been operational off the coast of Chukotka for a few years, now. The new agreement suggests that Russia intends to build out that prototype into a program. The idea may be getting traction in other countries, too. Last year, a symposium on the subject was held by the International Atomic Energy Agency, which noted an increasing "interest from Member States and industry to consider floating nuclear power plants," whether for electricity generation, or for desalination, or to extract hydrogen from the sea. An Indonesian participant at the symposium said that such plants would be "an interesting option for Indonesia as many power or utilities companies have floating diesel power plants or floating gas power plants.”

The first Russian floating nuclear power station, Akademik Lomonosov, being transported, 23 August 2019. ©Elena Dider

The idea of putting an atomic reactor on a floating platform at sea, exposing it to the chaos of waves and weather, might seem crazy (and, certainly, it has come in for criticism), but it has been around for many decades. It's been a pet fascination of mine, because early in my journalism career, an editor at the Village Voice—hoping to encourage me to approach my reporting in a meticulous way—told me to go read John McPhee's "The Atlantic Generating Station," a piece that ran in The New Yorker in 1975, and was anthologized in Giving Good Weight. It is about an engineer's (failed) dream to build a floating-nuclear plant on the eastern seaboard. McPhee begins with the line: "The Atlantic Generating Station was first imagined early one morning in 1969 by a man in Westfield, New Jersey, who happened at the moment to be taking a shower before dressing and going to work." He continues in that vein, his prose so precise, so neutral—shaped so thoroughly by his curiosity and love of detail—that it is hard to know if his descriptions are of engineering or environmental problems. Take this, for example:

"Certain questions had to be considered, though. While cooling themselves, the floating nuclear power plants would suck in more than two million gallons of seawater per minute. Screens would cover the ingress. What would happen to fish drawn toward the screens? What kinds of fish would they be? At what speed should the water be sucked in? What should be the size of the mesh? Phytoplankton, zooplankton, larval fish, and other small creatures would go through the plant. What percentage would die? The water would increase in temperature seventeen degrees. Biocides would be injected into the plumbing to keep it clean. After four minutes, the water would be returned to the ocean. At discharge, how fast should it come out, and at what level?"

McPhee has written a lot about geology, so maybe it's apt to flag this item, too: the discovery of four massive underwater mountains off the coast of South America. Scientists were apparently investigating subtle perturbations in Earth's gravity when they encountered them. "The tallest is over one-and-a-half miles in height, and we didn’t really know it was there," a researcher later pointed out in New Scientist. The story is a reminder that even though the oceans cover the majority of the planet's surface, there is still so much we don't know about them. File it alongside this headline, from last year, in the Miami Herald: "A golden egg? Mysterious shiny orb seen on seafloor off Alaska stumps ocean explorers." The specimen was discovered in the abyssal depths near Alaska during a NOAA expedition. “I just hope when we poke it, something doesn’t decide to come out,” one scientist confessed. “It’s like the beginning of a horror movie.”

Unidentified specimen, seen in situ on a rocky outcropping at a depth of about 3,300 meters (2 miles). ©NOAA Ocean Exploration, Seascape Alaska.

Hakai Magazine just posted a story about a geoengineering proposal, developed by Douglas Wallace, an oceanographer at Canada's Dalhousie University, to revitalize ocean dead zones. "In the Gulf of St. Lawrence—where the size of the dead zone has grown nearly sevenfold since 2003 to encompass roughly 9,000 square kilometers—dropping oxygen levels are already affecting many commercially important and at-risk species, such as cod, halibut, and northern shrimp," the story notes. In the deeper parts of the Gulf, a significant fraction of the water is so oxygen-starved that it is barely habitable for some animals. When Wallace learned that Canada plans to isolate hydrogen for fuel, he had an idea: oxygen is a chemical byproduct in hydrogen production, so why not inject it into the marine dead zones? It is an ambitious idea, and whatever the calculations on paper suggest, the practical obstacles might be enormous, and real-world outcomes hard to predict. As Wallace and his co-authors concede, "No aeration system has been designed, developed, or tested for the depths and scales considered here."

Lastly, mariners traveling in the direction of Antarctica have long known about the perilous seas at the bottom of the world, where some "rogue" waves can reach immense proportions. (A few years ago, a buoy in the Southern Ocean measured one that had achieved a staggering height of eighty feet.) A number of specialists in fluid dynamics have tried to work out statistical calculations that explain how these strange outliers form—and the emergence of competing models has even prompted some mathematicians to seek a "unified explanation to rogue wave formation." A new paper, "Observations of Rogue Seas in the Southern Ocean," documents an attempt to understand the phenomenon differently: by getting into a ship, heading into bad weather, and looking. “Rogue waves are colossi—twice as high as neighbouring waves—that appear seemingly out of nowhere,” Alessandro Toffoli, the lead researcher on the paper has noted. "Stories of unimaginable mountains of water as tall as ten-story buildings have populated maritime folklore and literature for centuries." With sophisticated cameras, Toffoli's team was able to create 3D images of waves, and determined that wind is a primary driver of the anomalous behavior, especially as it affects waves in their early formation. And the "rogues," it turns out, may not be so rogue. "We recorded waves twice as high as their neighbors once every six hours," he added. Whether this news is cause for alarm, or for comfort, in a world that might be powered by many new floating atomic reactors was not addressed in the study.