Humpback Whales Blow Bubble Rings

Guest Blog by Jodi Frediani

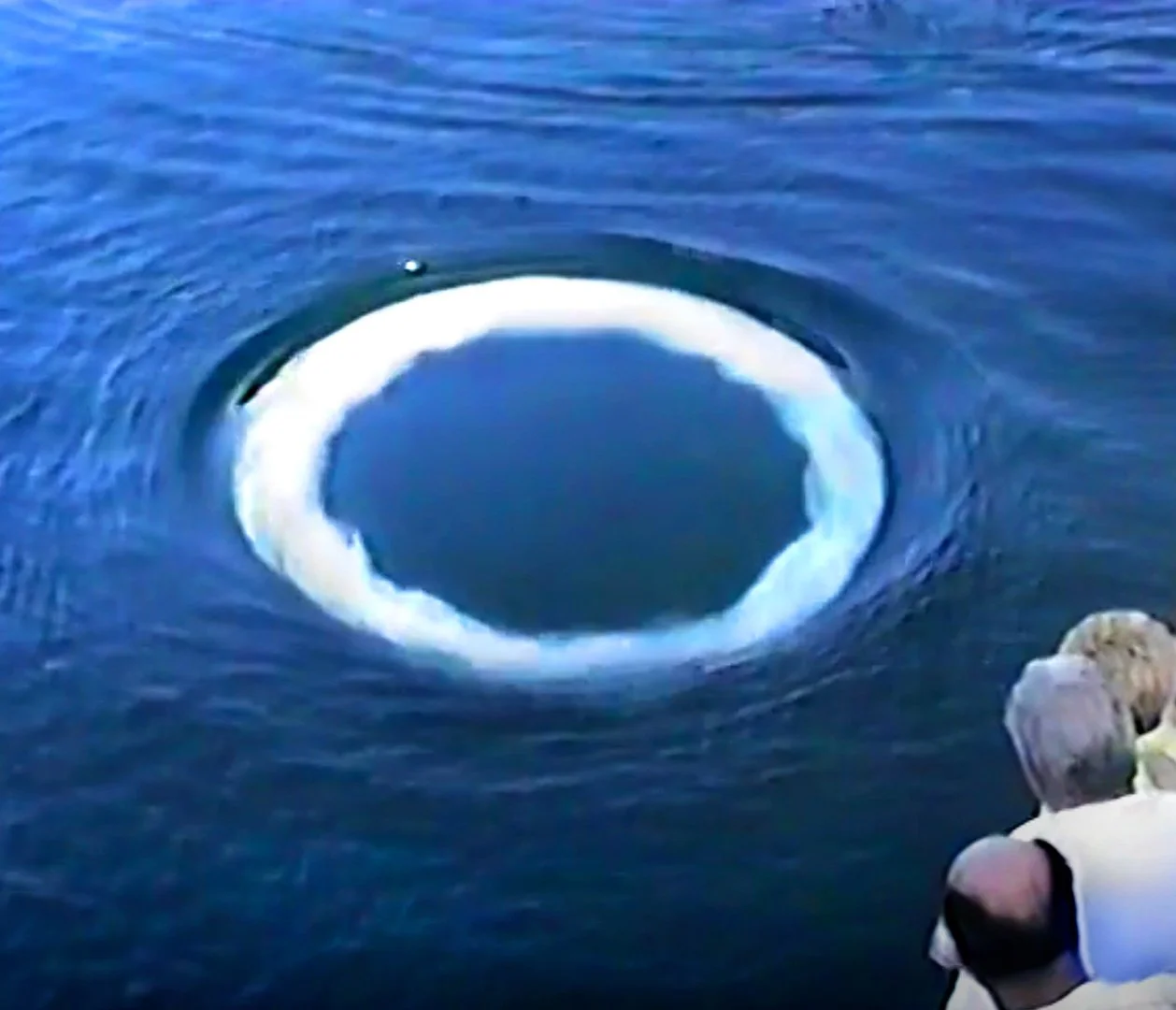

A bubble ring blown by a humpback whale. ©Dan Knaub, The Whale Video Company

What would you think if a humpback whale approached your whale watch vessel and blew a perfect bubble ring, like a smoke ring in the water, right next to the boat? Unlikely to happen? Maybe, except we’ve now uncovered more than a dozen encounters where humpback whales have voluntarily approached boats and swimmers then released one or more bubble rings in their presence.

Some of you may know people who blow smoke rings as a sort of playful parlor trick to test their skill and entertain their friends. Other talented folks, like a friend of mine, blow bubble rings underwater, also for good fun and entertainment. Me? I can barely whistle! So, are these whales also just doing it for fun and entertainment, or might there be another reason?

Along with my colleague, Dr. Fred Sharpe, our interest was piqued after finding an online video of a humpback whale that was known to approach boats and blow bubble rings back in the late 1980s. If you had been a passenger on a large whale watch vessel off the coast of Massachusetts on Stellwagen Bank back then, you might have been among the first to see that young whale, who was named Thorn, blow a series of remarkable bubble rings, sometimes even interacting with them.

©Dan Knaub, The Whale Video Company

On that day, after breaching a short distance away, Thorn made a beeline towards the vessel and spent the next 10 minutes or so alongside, producing a series of very large smoky-looking bubble rings. The passengers hooted, hollered, and stamped their feet on deck in appreciation of the interspecies entertainment. But was this just a whale being playful? Did he appreciate the human response? Or were those rings a form of communication specially directed at humans? Was Thorn just an anomaly, or did other whales blow bubble rings, too? We wanted to see if we could find out.

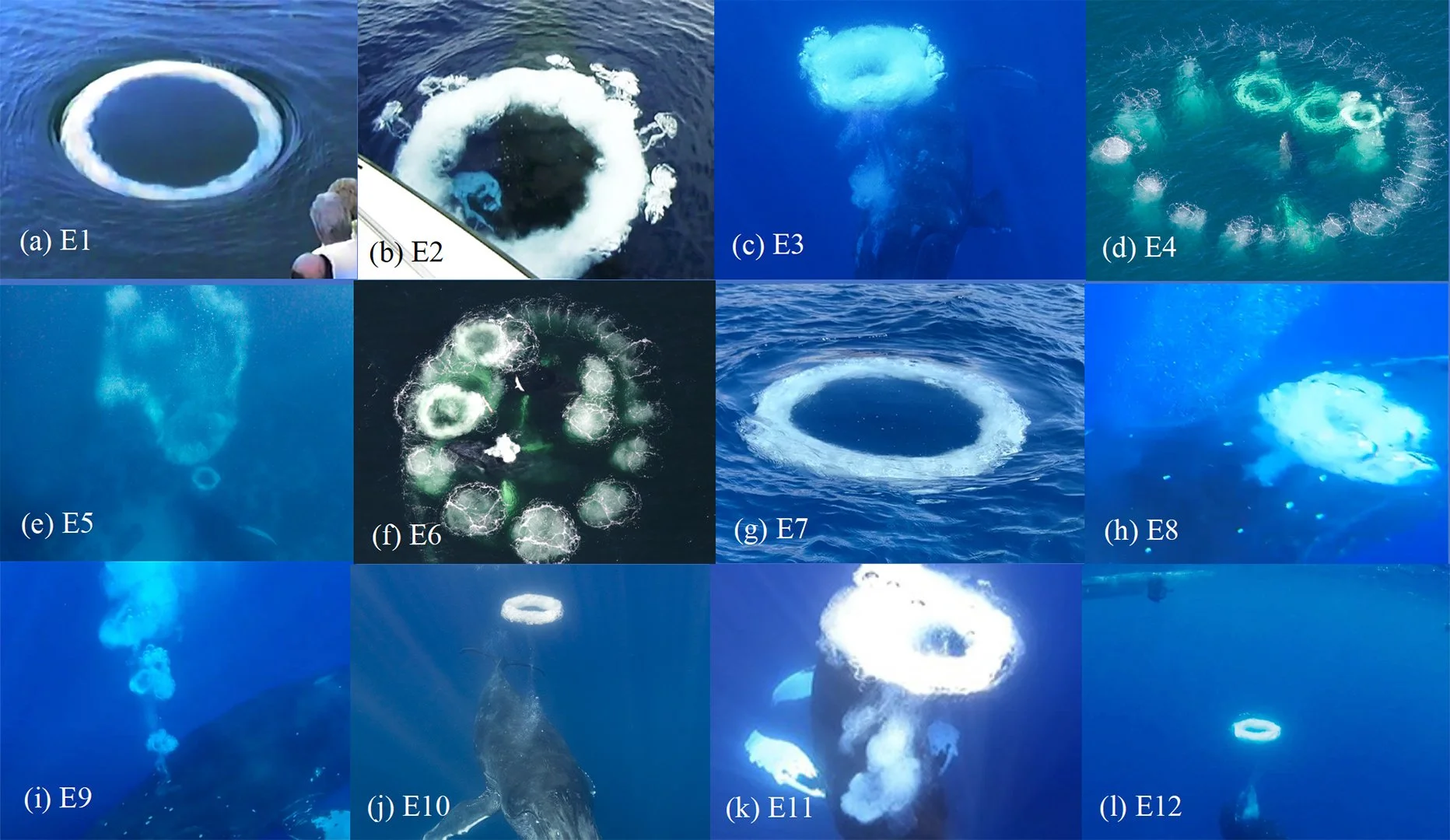

As we began an exploration of this curious behavior by a solitary whale, our search led us to 12 individuals in three oceans, on both breeding and feeding grounds, that had been captured on film and video releasing bubble rings. Most of them voluntarily approached boats or swimmers in a leisurely fashion, sometimes exhibiting typical ‘friendly’ behavior such as spy hopping, rolling languidly, playing with kelp nearby, or slowly raising and lowering their tails. Then the whales would surprise the nearby humans by producing one or more bubble rings. One whale, accompanied by a second, hung below a group of swimmers and released a bubble ring beneath them. And two more whales blew rings inside bubble nets created to corral fish.

Composite image of at least one bubble ring from each episode. Photo attributions are as follows: (a) D. Knaub, (b) F. Nicklen, (c) D. Perrine, (d) W. Davis, (e) G. Flipse, (f) A. Henry, (g) M. Gaughan, (h) H. Romanchik, (i) D. Patton, (j) D. Perrine, (k) S. Istrup, (l) S. Hilbourne.

Such rings were first described by Roger Payne, the man who introduced the world to humpback whale song. In his book Among Whales, he described bubble rings as “madly spinning doughnut-shaped clouds that look like giant smoke rings about three feet in diameter that rise rapidly to the surface”. Other than Roger’s anecdotal account, however, there was nothing in the literature about humpback whales creating these fascinating bubble structures.

Humpbacks are, however, widely known for their tool use of bubbles, creating bubble nets to corral small forage fish or krill during feeding. These nets are comprised of individual bubble bursts released by a single whale swimming in a spiral. In some instances, particularly in Antarctica where humpbacks feed on krill, multiple whales will create a net of concentric spirals, likely providing a denser bubble barrier to contain the smaller prey.

Less well known, but equally common, is humpback whale use of bubble blasts, bursts, and trails in male-male competitive groups, while vying to escort a female. This behavior is generally observed on the breeding grounds. Those forcefully released bubbles seem to be used to intimidate other competing males and possibly impress the female. A ‘rowdy’ group, consisting of a female, her primary escort and one or more challengers, tends to move fast, with some males bashing others, some doing brisk tail throws to keep challengers at bay, along with other aggressive and often antagonistic behavior.

©Jodi Frediani

Some of those bubble trails, when blown beneath the surface, act as a screen to obscure the female from the challenging males.

Also on the breeding grounds, a recent study described a female humpback whale who positioned her genital area over a release from the blowhole of champagne-size bubbles generated by a male escorting her. Likely this was a sensual experience for the female and part of a courting ritual.

With the ability to blow bubbles both small and large, in single bursts, clouds, and continuous trails, bubble rings can now be added to the humpback whale’s extensive bubble repertoire. But just why they do it, and largely in the presence of humans, is still a mystery. To try to understand their motives for blowing bubble rings, we explored inquisitiveness, foraging, resting and aggression. Our research indicated that a good hypothesis may include curiosity, play and/or interspecies communication. However, humpbacks seem to use rings in multiple contexts.

Dolphins in captivity have been long known to blow bubble rings for play, while some of their wild counterparts have used them for other purposes. Dolphin rings encapsulate a single bubble of air, producing a clear, precisely outlined ring. They may blow rings from the mouth or blow hole. Bubble rings blown underwater by humans are similarly formed from a single clear bubble of air. And both species are known to swim through their rings. Dolphins are talented at interacting with their creations and using their beaks to fashion smaller rings out of the one they released from their mouth. They are even capable of creating rings using their tails to smack the water just so. The rings blown by humpback whales exclusively from their blowholes are, not-surprisingly, much larger, but are filled with lots of tiny bubbles, creating the smoky appearance.

In our examination of documented ring reports, we were able to discount aggression as motivation for producing bubble rings. Most of the whales voluntarily approached boats or swimmers then released their bubble-creations in front of their presumed intended audiences. Some of those whales were also known for prior friendly behavior towards boats. Often the ring-blowing whales were by themselves or, when accompanied by other whales, did not show any aggressive behavior.

A friendly humpback watches whale watchers at the rail. ©Jodi Frediani

We also examined feeding as a possible motive. In two episodes captured by light planes, bubble rings were blown inside a spiral bubble net on the feeding grounds. Presumably, the rings helped the whales in their efforts to catch fish. However, in the rest of the episodes there was no prey visible, no birds or other predator species such as sea lions indicating a food source nearby, and no ventral pleat expansion or fish visible that would indicate feeding. In fact, nine of 12 episodes took place on the breeding grounds where food is scarce and opportunistic feeding rarely occurs. However, from our very small sample size it appears that rings may be used to enhance bubble net effectiveness.

We were also impressed that all the whales, except those feeding, exhibited this ring blowing behavior in the presence of humans. In those 10 episodes, humans seemed to be the intended recipients of the ring releases. To confirm that this wasn’t simply observer bias (e.g., bubble ring blowing would only be observed when whales were close to boats), we consulted with several researchers using drones (UAVs) in their studies. No rings were observed in nearly 5,000 drone flights away from boats.

According to acclaimed animal trainer Karen Pryor, who began her career working with dolphins, “Patterns of bubble production in cetaceans constitute a mode of communication not available to terrestrial mammals.” Observers have noted that birds like the honey guide use a specific call reserved for human honey hunters, and zoo-housed gorillas use species-atypical vocalizations to attract the attention of their human caretakers. So, perhaps our ring blowing whales are attempting to communicate with us using unique bubble creations. We would love to test this possibility. We hope to create a bubble-ring generator and deploy it in the presence of friendly humpback whales. Then if a whale responds in kind, we might be able to engage in a bubble ring communicative exchange. Separating a playful intention from one meant to solely communicate information might be challenging, but one needs to start somewhere.

In May of this year our paper, Humpback Whales Blow Poloidal Vortex Bubble Rings, was published in the journal, Marine Mammal Science. Since then, five more ring-blowing episodes have been brought to our attention, one in Antarctica, two in Monterey Bay, CA another on the Silver Bank, Dominican Republic, and one in Mexico. We are excited to continue to explore this curious behavior and hope more accounts will surface now that people know what to look for.

Our team members in this effort included Dr. Fred Sharpe, co-lead author, humpback whale researcher; Jodi Frediani (that’s me), co-lead author, photographer at Jodi Frediani Photography and humpback whale researcher; Dr. Josephine Hubbard, UC Davis postdoctoral researcher specializing in animal behavior, communication and intelligence; Doug Perrine, photographer at Doug Perrine Photography; Simon Hilbourne, photographer, videographer with the Marine Research Facility; Dr. Joy Reidenberg, anatomist at the Center for Anatomy and Functional Morphology at the Icahn School of Medicine, at Mount Sinai; Dr. Brenda McCowan, UC Davis professor of ethology; and Dr. Laurance Doyle, astrophysicist with SETI who employs information theory to understand the meaning of animal vocalizations.