Stories of the Sea - Worries over AMOC

By Safina Center Historical Journalism Fellow Raffi Khatchadourian

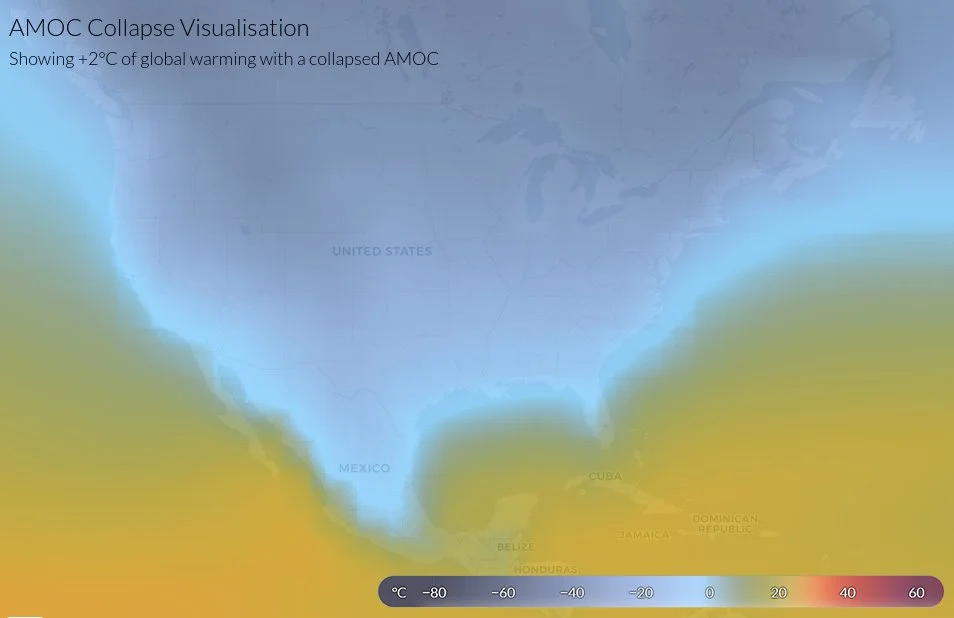

A screenshot of an interactive map used to visualize the effects of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation’s (AMOC) potential collapse. This specific map depicts expected temperatures during an extreme cold event in the United States if the AMOC collapses. Via AMOCScenarios.

Like a vast, looping, liquid conveyor belt, a series of ocean currents called the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) snakes around a large part of the Earth, causing warm water from the Gulf Stream to circulate northward, while cold water is pulled in the opposite direction. Although confined to the sea, the countervailing flows have a stabilizing impact on the entire climate. The chance of them substantially changing, breaking down, or reversing, have long been regarded as "one of the most dangerous climate tipping elements."

With that in mind, some recent stories about the AMOC earlier this year caught my eye.

In June, scientists at Utrecht University, in the Netherlands, modeled changes to the climate if the currents were to weaken, or break down, due to global warming. It is generally thought that a breakdown of the AMOC would cause cooling; explaining the study's intent, the lead author told CNN, “What if the AMOC collapses and we have climate change? Does the cooling win or does the warming win?” Many people tend to think that climate change will uniformly mean a warmer planet, but the climate system is so complex, volatility may make things colder.

Earth's atmosphere is currently around 1.2 degrees Celsius warmer than its pre-industrial climate. The Utrecht researchers, René van Westen and Michiel Baatsen, explored what it would mean if the AMOC were to substantially break down, while Earth's climate warmed to 2 degrees Celsius. It turns out that in such a scenario, parts of the Northern Hemisphere—the study focuses on Western Europe—would likely experience "profound cooling."

The authors of the study created an interesting interactive map to demonstrate the model's predictions under different conditions. With 2 degrees warming, New York City, for instance, might experience severe winters, with temperatures that could plummet to -23.2 C (-9.76 Fahrenheit). A city like Oslo could see days where the temperature dropped as low as - 55 Fahrenheit. As a scientist with the University of Exeter who reviewed the data told the publication Carbon Brief, “The extreme winters would be like living in an ice age. But at the same time summer temperature extremes are barely impacted—they are slightly cooler than they would be due to global warming, but still with hotter extremes than the pre-industrial climate."

The Utrecht model assumed that the AMOC would reach a point of breakdown that they called a "tipping point." Currents in the Atlantic are indeed slowing already, but there is still considerable uncertainty about how much they will change with a warming planet. This May, researchers at Caltech ran a model that predicted the AMOC will "weaken by around 18 to 43 percent at the end of the 21st century," which suggests it might behave with some resilience. However, other models have charted a far more rapid and severe course of degradation—with one recent study positing that the AMOC might weaken by a third within the next fifteen years.

There is little question that changes to the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation could have planetary impacts. At the same time, making predictions about Earth-spanning movements of seawater is obviously a challenging undertaking. There are still many unknowns, and a lack of scientific consensus, but as one climate researcher told CNN about the Utrecht findings, “Even the mere possibility of this dire storyline unfolding over coming centuries underscores the need to forensically monitor what is happening in our oceans.”